The award-winning writer talks with us about his debut novel’s nuanced intimate view of slavery, why he focused on the development of the female characters, and how he got Joe Morton to bring this gem to life.

Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly. PLUS: Bonus content at the bottom of the text.

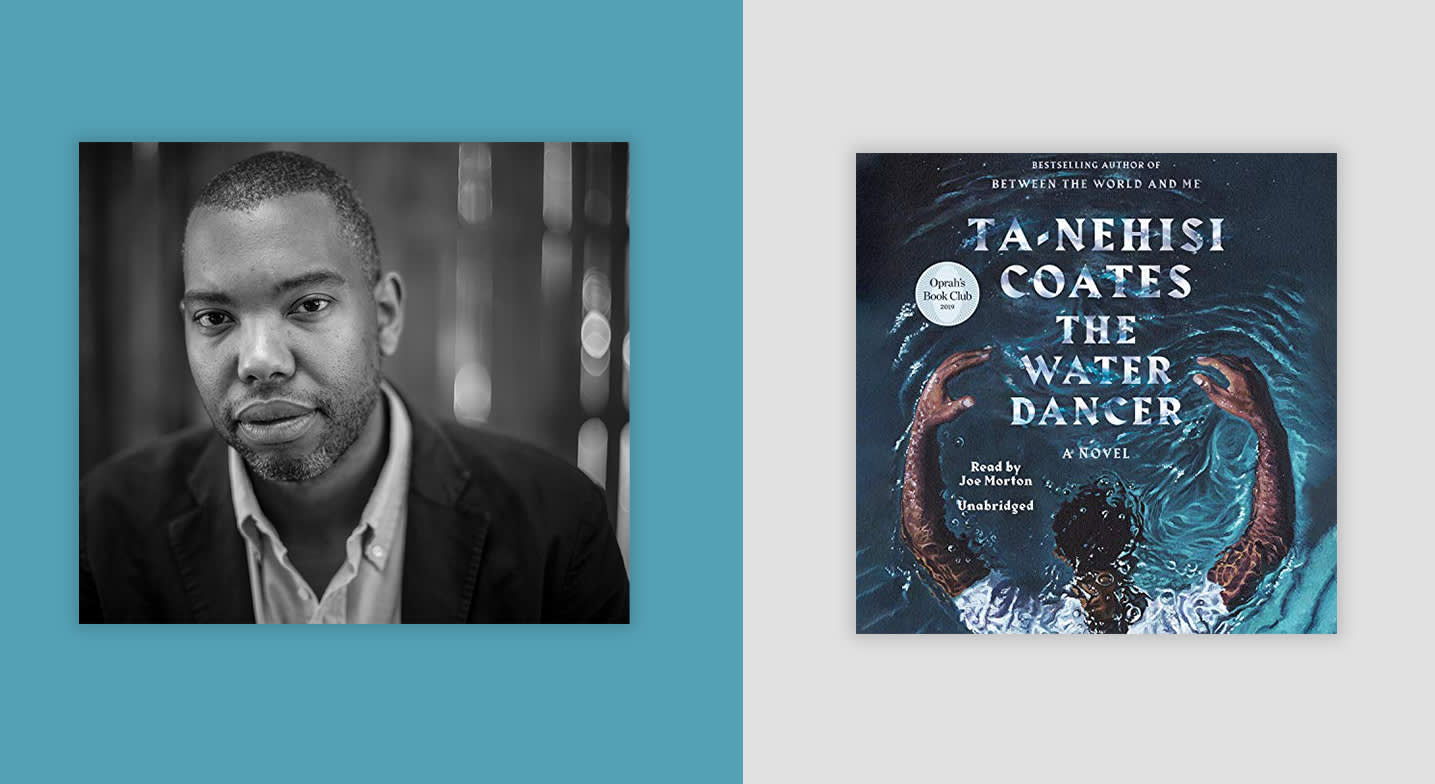

AW: Hi, I’m your Audible editor, Abby West, and I am thrilled to have Ta-Nehisi Coates talking to us today. He’s the best-selling author of The Beautiful Struggle, We Were Eight Years in Power, and Between the World and Me, which won the National Book Award in 2015. Ta-Nehisi is a distinguished writer in residence at NYU’s Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute, and he is a recipient of a MacArthur fellowship. He has also written Marvel comics The Black Panther and Captain America. But today we’re going to talk about his beautiful first novel, The Water Dancer. Welcome, Ta-Nehisi.

TC: Thanks for having me, Abby.

AW: I’m truly delighted to because I got to do an early read and early listen of this book, and it has been so difficult not to spoil it as I try to tell everybody how amazing it is. And even as I’m about to describe it, I am dancing around the language because I really want people to discover what happens on their own and not have it spelled out because there was a lot of beauty in that for me.

So it’s about Hiram Walker, an enslaved man in antebellum Virginia. He’s the son of a white plantation owner and the woman who was his property. But from the beginning, Hiram exhibits unique abilities, such as a photographic memory, and another gift that would later manifest as he becomes more involved in the Underground Railroad. That’s my spoiler-free way of talking about it, but it is so much more. And I really want to talk to you about how this came to be. Where did the story start for you?

TC: I think the short and easy answer is it started at the end of The Beautiful Struggle after it was published. Well, as it was turned in. My editor, Chris Jackson, and my agent, Gloria Loomis, both of them thought I should try fiction as the next project. And I began fishing around to figure out where that fiction would live. It just so happened to coincide with the point where I was doing a tremendous amount of research on the epic of enslavement and the Civil War. And as I did that, characters and scenes and settings started to come to me, which eventually, after a 10-year process, resolved themselves into The Water Dancer.

AW: How many rewrites did you have on this book?

TC: I think it was four; we made four versions.

AW: And at least one of them where you scrapped it down to like a paragraph or two and started again.

TC: Yeah, I think out of the third one about a paragraph or so, maybe more, of it survived, but not much. And I’m wanting to say, I don’t know, two or three percent of what the book is now. That was last year.

AW: Wow. That’s really amazing. I think there’s so much here. Would you say that it’s been sort of percolating while you may have restarted the process, but that was all built on the foundation of the other works that you started?

TC: Yeah. I think what this book has shown me is, especially when you’re talking about bigger books, the importance of taking your time and letting things just marinate. Because a couple things happened with The Water Dancer. I think… I became a better prose writer, period, over the course of those 10 years. Just doing the other projects I was doing. I got to spend time with Hiram and Sophia and Caroline and Corrine and Dana and Hawkins and Amy, and they all got to live with me for a relatively long period of time, just to sit there. Even when I wasn’t working on it, I would think about them all the time. And I think that actually shows in the book, the fact that there was just a tremendous amount of time taken with each character.

AW: So they became more real in your head the longer it went on, the longer you were in the process.

TC: Exactly.

AW: To that end, how was it different for you approaching this work of fiction from your nonfiction work, which you’re so well-known for?

TC: In nonfiction, at least after you do your reporting and your research, you know the story. But [with] fiction, you just don’t know. A lot of times what you outline in fiction as the story doesn’t actually hold up. I think it was E. L. Doctorow who said, “It’s like driving down a dark road and you can only see as far as the headlights go.” So there’s a lot. I think about a character like Thena, who, in the last draft before the one I finally turned in that became the book, she was a very, very different character. Just in the rewriting, I became more interested in a different version of her. If I’m writing a nonfiction piece, the people I interviewed are people I interviewed. That’s not going to change, unless I get wholly new people. But the people themselves, they’re not going to change. But in fiction, it’s a little different.

AW: Yeah, you get to evolve them. And I can’t imagine Thena any differently than the way you wrote her.

TC: I think you got the best version of her.

Joe Morton is incredible. [His narration is] amazing. I was listening to it in the house the other day, and at a certain point I forgot I wrote it.

AW: That’s great. Now, I love magical realism for the ways that it both grounds you and envelops you. And the way you use it to such great effect here is pretty magnificent. I’d love to hear about your influences in taking that route.

TC: It’s a couple of things. I’ve always had an attraction to fantasy literature and science fiction literature, movies, et cetera. But more than that, it was an attempt to take the world of being a slave for real. If you read narratives from that period, there are always these references to some sort of mysticism or magic. Frederick Douglass and how when he makes his escape, he gets a special root that’s supposed to help him tell the enslaved about things they can do to inure them against bloodhounds, or whatever, when they’re running. Just all sorts of things. So this was really an attempt to take the world as enslaved people had sketched it, which was a mystical world to them, and render it in a serious fashion.

AW: I love that. Can you talk about how you approach the different nuances here? You talk about the Virginia society with the task system of slavery, which is very different than what is going on in the deeper South. And you talk about the nuances of Hiram’s station as a tasking man. We can come back to and explain the tasking element. Connected by blood to his “owner” and seemingly disconnected from his mother, who has been sold off. There are so many nuances here. Was that top of mind for you, or did it just come through as you were writing?

TC: It came through as I was writing, but it has to be refined. It has to be rewritten. You have to get the specifics down. Once again, that’s why it takes a second. But I think those nuances are things that make it feel like a fully realized world. So those things weren’t optional to me; they really just had to get done. But I had the benefit of time. And I had the benefit of good editors and good readers to help me.

AW: I think you crossed the bridge for so many people, me included, who sometimes lament not having gone to an HBCU and gotten the deep immersion into our history that you did and that your beloved Howard University gave you. But the idea that people have one sense of what slavery was, and within this book and a few others, but this one really brings it home, how there’s this hypocritical look at slavery in society where everything was polished off so you couldn’t see the horror of it all.

TC: I should make something clear. The term “the tasked” or “the task,” which I used as basically a synonym for slavery in that period, is derived from, as you said, the task system of slavery, which was present in places like South Carolina, for instance. In other words, I’m repurposing that word differently. Having said that, you are correct. It’s a different thing going on. In Virginia, there is a loss of arable land that’s taking place. And so there’s less room for cash crops to be harvested from the soil. Whereas in the deep South during the period of this novel, there’s an expansion of land. And what is needed is people to work that land. That’s the economic conflict. The result of that means that enslaved people in the upper South are being sold and transported into the deep South. What the novel is interested in is the effects of that, specifically the psychological effects on enslaved people and on the tasked, and on their families and on the effects of family separation. Which is what our lead character, Hiram Walker, and several other characters in the novel, suffer under.

AW: You do such a great job with their interior lives and sketching them out in fullness, and not just their station. You also go on to invoke the great Harriet Tubman here, and she is essential in Hiram coming into his power. Was this part at all more daunting than the entire endeavor, drawing this great historic figure to life?

I wanted interesting, complex, thick relationships in the book. And for that to be, I think that it necessitates you depicting your characters as human beings, and that includes women, obviously.

TC: No, you know what I had to do? I just had to think of somebody. Once I had attributes of a real person, I just drew from there. I always thought of Harriet Tubman—and I’ve said this before—like she’s the Gandalf figure in the novel, or the Obi-Wan Kenobi. She’s the old master, even though she’s actually not that much older than Hiram in the novel. She’s the one that’s much more acquainted. She has a hard-edge kind of realism. And I pulled that from reading about her and history. You’ll see little things that can tell you something about somebody’s personality. There’s a story about how John Brown was so impressed with Harriet Tubman that he tried to recruit her to go on his raid on Harper’s Ferry. And she just declined. She said, “That’s crazy. I’m not doing that.” So the feeling was that, in addition to the mysticism [surrounding her], there was a kind of real pragmatism, a cold practicality about this figure. And knowing that, I could derive quite a bit from her.

I also enjoyed the fact that as she’s depicted in the novel, she’s legendary in her own time. The other enslaved people feel like she’s legendary when they see her. But she doesn’t see herself as legendary. She’s like, “Listen, I’m about this business. I’m about this work.” And they have all these other names for her—the Vanisher, Moses on the Chesapeake, all these names. And she’s like, “Listen, man. I’m not paying any attention to any of that. This is what I do.” You know what I mean?

AW: “I answer to one name.”

TC: Right, exactly. “And I don’t indulge in all these other stories or any of that. I just do X, Y, and Z.” So that, I think, was taken to some extent from the history, but also from the kind of figures that I was modeling her on. You rarely see women get to play the Gandalf or the Obi-Wan role. I just thought that was sort of cool and that was fun.

AW: Well, that brings me to another point. Ta-Nehisi, this is a legit feminist work. You know that, right?

TC: I don’t know that. That’s not something I would say. And not just out of modesty. I literally don’t know that. But I’ll take it. Thank you. I appreciate that.

AW: I will say it. Yep. Okay. I will say it. I’ll be the one to say it. Because you give all the women at various levels of station agency, and you give them a spirit that can’t be broken. But you also have nuanced emotion from Thena to Corinne, especially Sophia. You have Hiram, an enslaved black man, learning that to have the woman he loved, he had to understand he could never possess her. Why was this an important part of the story for you? And part two, were you making a statement for men today?

TC: No, you know what it is? This is probably in reaction to a couple things. I very much wanted The Water Dancer to be an adventure story. So it’s genre fiction in many ways. I wanted the meaning and the symbolism and all the depth and the thickness of a literary work, and I wanted the speed and the excitement of a piece of genre work, of a Western, of a great adventure story, of a saga, of an epic. And what really happened, Abby, was at the same time, I had had a long time—being that, at this point, I’m almost 44 years old—to absorb genre fiction. To think about Westerns and think about how women are presented in those. I’m a huge comic book fan. I think about what roles women play in those stories.

It is incredibly, incredibly common to have a situation wherein you have a hero and the woman is like a plot device. “I have to go save this woman, X, Y, and Z.” Or, “The bad guys raped and killed my wife, so now I have to go avenge them.” So I was aware of that. The second thing I was aware of is the deep sense with which Black men historically have felt shamed by their inability to protect Black women. I want to be clear about what I’m saying. When I say protect Black women, I almost mean protect them not even so much as people, [but] as objects. So there’s one level of wanting to be protected, while that would be nice. But the level I’m talking about is within the constraints of the society. It’s saying that part of the job of a man is to “protect his woman.” You understand? Not protect the partner, not protect the spouse. Do I protect my wife? Yes. Does my wife protect me? Yes. I don’t mean equal protection. I mean a kind of macho.

AW: Possessive.

TC: One-way protection. And because Black men have never really had the power to enjoy that, there is a tremendous fictional, fantastical need, I think, among a macho male ego to create those kinds of stories. You know, a large portion of blaxploitation comes out of that… I wanted to create a work of genre fiction in many ways, or influenced by genre fiction, but I didn’t want to recreate that. I didn’t want to recreate the gender components that often go with it. I was aware of that. I was deeply, deeply conscious of that. And so on the one hand, I wanted Sophia to be there and I wanted Hiram to desire freedom for Sophia, but I wanted Sophia to have her own notions of what freedom is. I was interested in those notions not necessarily matching up with Hiram’s notions.

I thought it would be really flat if it were basically a situation of, “Okay, I’m going to run and I’m going to take you with me,” and her just basically waiting around for him to do that. Because then, there’s no exploration of what the interior life was. Sophia was interesting to me… She likes Hiram just fine. Okay? But she doesn’t need another white man. You understand what I’m saying? She doesn’t need another man to own her in a way that she’s already owned. She’s not trading one master for another. And she’s really, really clear about that.

And I thought if I could do it that way, that would just be a much, much more interesting story. I won’t give anything away, but the reactions that Thena has to Hiram, which I think prove that the women in the book are not there to serve Hiram. I think they have legit relationships that are complicated, that are back and forth. They love Hiram. I mean, most of them. You can argue about a couple of them that don’t. I wanted interesting, complex, thick relationships in the book. And for that to be, I think that it necessitates you depicting your characters as human beings, and that includes women, obviously.

So I appreciate your compliment, but I just feel a little unqualified to bestow it upon myself.

AW: Fair. I’ll let you not do that, and I’ll be the one to do that. And I think anyone who picks this up and reads it and listens to it is going to get that. Let’s talk about listening to this, because I love your words. I love everything about how it plays out on the page. And then you also listen to Joe Morton doing the narration of your book. And wow. Ta-Nehisi, it’s amazing.

TC: He’s incredible. It’s amazing. I was listening to it in the house the other day, and at a certain point I forgot I wrote it. And that’s normal, if you think about it. Like Aretha Franklin sings “Respect”, but her “Respect” is very different than Otis Redding’s “Respect.” It’s a different thing she’s doing there. There were some conversations about me reading the book, but given who Hiram was supposed to be, I didn’t feel like I really had the chops to read that book. If it was an omniscient narrator, maybe I would have felt differently. But given that it was him talking, I felt like it needed to be somebody else to read it.

AW: Did you have input in choosing Joe?

TC: I did. I asked him. I asked Joe.

AW: What?!

TC: Yeah, that was my idea.

AW: I love that.

TC: Totally my idea. I wrote him and requested. I asked him, would he consider doing it? And I am endlessly grateful that he did. I had the luxury of meeting Joe, because he was part of a theatrical production for Between the World and Me. He was tremendous, and the crowd loved him, just adored him. And I could see why. He had a strength of character in the way he conducted himself. And also, I just feel like everybody knows Joe, right? He’s Black people’s favorite character. Joe’s been in everything. You know what I’m saying?

AW: Yeah. He’s Papa Pope from Scandal for so many people.

TC: Exactly. And he’s been like that all my life, you know what I mean? And he always kills it. He’ll appear in these roles in these movies. He’ll be in a film like Ali… and he’ll come on screen and just kill it real quick. He’s been like that for us for so long that I thought he brought a kind of gravitas that I just couldn’t bring.

AW: Well, so much of the work affirms the power of oral storytelling. I’m not surprised that you’ve put so much thought into how this work was brought to life in audio. What was it like for you when you did the narration for Between the World and Me? What was that experience like?

TC: I thought it was really important that I do that narration because it was so personal a work. And it’s hard work. We were on a collapsed deadline because they moved the publication up, so it was difficult. But I was very pleased with what it ended up as.

AW: Did it add any new dimensions of your work to read it in that way?

TC: I think so. I think hearing me read it adds a dimension to it because I wrote it and it’s me. It’s actually my voice that’s doing it, which is very different than The Water Dancer.

AW: You talk a lot about the power of memory and of knowing your history in the storytelling, but also the community aspect. In setting up Hiram to have this evolving, expanding understanding of things being beyond just himself, things being for his community, specifically freedom being for his community, it felt like a larger statement for the world right now. And I’m wondering if that’s the case, or if I’m just putting that forward.

TC: It’s not intentional. That’s derived out of the actual literature. One of the more stunning things to me—I mean, it seems obvious—is when you look at why people run, family always comes up. “I ran because they were getting ready to sell my daughter.” “I ran because they did sell my wife and I felt like I had no ties to this community anymore.” Family is a constant refrain of that. So what that means to me is that individual freedom was never freedom. It was always freedom tied to other people. It was always about a more communal sense. In addition to that—I guess in the back of my mind, and there’s a scene that sort of reflects this—the black struggle has always been tied to other struggles. So it’s never been just us. And so it felt like that made sense.

AW: Got it. That makes sense to me. Now, has this whet your appetite for more fiction, for more speculative fiction and literary fiction?

TC: Definitely. I really enjoyed the process of writing this book.

AW: Are you already working on the next one?

TC: I’m always taking notes. But I’ve got to figure out what’s up next.

AW: Okay. Everything is fodder, right?

TC: Yes, it is. Very much so.

AW: Well, I can’t wait for more people to get to read this. Someone I work with leaned over earlier and said, “I finished the first chapter yesterday. Oh my God, it’s beautiful. I was hoping it’d be good. It was even better than good.” And that’s the kind of reaction I expect to hear from other people as they come along and read it and then listen to it. When Joe Morton breaks out into song, I think some folks are just going to…

TC: Incredible.

AW: Yeah, it’s an automatic favorite for the year, and I’m really excited for it to get out there. Thank you for talking with me today, Ta-Nehisi. I really appreciate it.

TC: No problem. Thank you, Abby.

SPOILER: Ta-Nehisi Coates discusses an alternate

ending he considered for ‘The Water Dancer’